|

|

Video

Transcription By:

Lori A. Eley, RN

Wife of Physician afflicted with RSD / CRPS

Advocate in support of Research and Cure for RSD / CRPS

|

RSD

IN CHILDREN

|

| Sarah

Young |

Sarah Young:

I want to be a normal teenager.

TV News narrator:

17 year old Sarah Young's battle with RSD, or,

Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy Syndrome, began

when she was hit with a softball.

|

| Sarah

Young's Mother |

Sarah's mother:

It took a while to show up, what it was, after

going through multiple doctors who did not...

they were clueless. I had a couple tell me to

cut her leg off, because her leg would be so

blue and ice cold.

UPDATE

September 2007

Nearly three years later, Sarah gave birth to two children

Click HERE

|

TV News narrator:

RSD develops after the body experiences a trauma.

The Sympathetic Nerves, ones that prepare the

body to react to emergencies, misfire and send

constant pain signals to the brain.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

The mechanism by which an injury triggers RSD

is unclear. The following animation is intended

to give a simplified view of how a relatively

minor injury might lead to RSD. Activation of

the Sympathetic Nervous System following an

injury is part of the fight/flight response

to an emergency situation. This response is

very important for survival.

For example: Firing of the sympathetic nerves

following an injury causes the blood vessels

in the skin to contract, allowing blood to be

shifted to muscle and vital internal organs,

which enables the victim to use his muscle to

get up and escape from danger. Also, decreased

supply of blood to the skin reduces blood loss.

Thus one might expect the skin to turn from

red, due to inflammation, to pale, due to decreased

blood flow following injury. Also, because the

Sympathetic Nervous System causes increased

metabolism and heat production, there is increased

sweat production to cool the body. Ordinarily,

the Sympathetic Nervous System shuts down within

minutes to hours after an injury. The Sympathetic

Nervous System exerts control not only of the

injured part, but of other parts of the body.

Early in the course of RSD, this Regional and

Central control is lost and there is increased

blood flow to the injured area and other parts

of the body. For reasons we do not understand,

individuals who develop RSD the Sympathetic

Nervous System appears to assume an abnormal

function. The sympathetic outflow appears to

cause pain by directly stimulating receptors

on pain fibers. These events are believed to

produce more pain, leading to more stimulation

of the Sympathetic Nervous System, which triggers

another response establishing a vicious cycle

of pain. Thus, we might see changes over time

directly attributable to a abnormal function

of the Sympathetic Nervous System. These changes

include: changes in skin temperature, changes

in the color of the skin, red or bluish discoloration,

changes in sweating, changes in goose flesh

or Piloerection of the skin, and swelling. Most

patients with RSD have more pain expected for

the type of injury they have suffered. They

usually have swelling and discoloration early

in the course of the disease.

Objective Findings

Dr. Kirkpatrick: There

are two important things to remember about the

objective findings sometimes seen with RSD.

First, none of these objective findings for

RSD might be present in a patient with RSD,

especially during the early stages of the disease.

Second, these objective findings tend to be

labile, meaning that they may come and go over

time.

Movement Disorder

These abnormal changes in

the Sympathetic Nervous System seem to be responsible

in some patients for constant pain signals to

the brain. Abnormal function of the Sympathetic

Nervous System leads to Movement Disorder. Pain

is not the only reason why patients have difficulty

moving. Patients state that their muscles feel

stiff and that they have difficulty initiating

movement.

Sometimes blocking the Sympathetic Nervous System

with local anesthetics injected near sympathetic

nerves can lead to a prolonged reversal of this

abnormal sympathetic function, resulting in

improved movement and prolonged relief of pain.

We call this Sympathetically Maintained Pain.

In other cases the pain returns after a series

of sympathetic blocks. In this situation, it

might be possible to obtain a permanent relief

of pain and improve movement by selectively

destroying sympathetic nerves. We call the selective

destruction of sympathetic nerves a Sympathectomy.

In some patients with RSD, blocking the Sympathetic

Nervous System provides little or no relief

of pain. We call this Sympathetically Independent

Pain (SIP). These patients, nonetheless, might

manifest all the findings of abnormal function

of the Sympathetic Nervous System previously

stated.

As RSD progresses over time, especially without

treatment, the disease tends to become more

sympathetically independent and unresponsive

to sympathetic blocks, hence, the importance

of early diagnosis and treatment of RSD. However,

there are some patients who appear to have RSD

that is sympathetically maintained pain (SMP)

for a lifetime, and these patients maintain

a positive response to sympathetic blocks.

|

| RSD

can spread |

RSD can remain localized

to one region of the body indefinitely. In other

cases, it can spread to other regions of the

body spontaneously or by trauma to other regions

of the body.

For example: In this illustration, RSD has spread

spontaneously to the opposite upper extremity

and to the lower extremity. RSD of the upper

extremity can spread to the face causing problems

with hearing and seeing. Also, RSD of the upper

extremity is sometimes associated with difficulty

in swallowing. RSD of the lower extremities

can be associated with bowel and bladder problems.

Thus the term Total Body RSD has evolved over

the years as we learn more about this disease.

Special Considerations

In Children

Male Narrator:

Pediatric patients present unique challenges.

For example: Children have not had sufficient

time to develop the psychosocial skills necessary

to cope with the pain and suffering due to RSD.

Also, children generally fear needles more than

adults do. Needles are the basic instrument

used to perform sympathetic blocks. This fear

and anxiety in children leads to a lowering

in the children's pain threshold, making nerve

blocks and other medical procedures even more

painful.

Another concern in children relates to cosmetics.

Children might have a greater concern for scar

formation following surgery. These concerns

have led to a great deal of confusion and frustration

among children and their families.

Although there have been no large-scale studies

on the incident of RSD in children, some generalizations

can be made about the children who get this

condition. Published case studies indicate that

the incident of RSD increases dramatically between

9 and 11 years old, and it is found predominantly

in young girls.

During this program we will learn a great deal

about RSD through the voices of children. The

two children in this program are typical for

children who get RSD. Both are female and both

are aged between 10 and 14 years old. These

two children were chosen for another important

reason. These two cases illustrate that not

all RSD is the same. There could be great variability

in the clinical course of the disease as well

as in the response of the condition to treatment.

This variability in RSD has led some to speculate

that there might be different subsets of patients

with this disease.

This videotape has been prepared in consultation

with Dr. Anthony Kirkpatrick and Dr. Dennis

Bandyk. Now please consider this situation:

|

| Lacey

Booth |

A ten-year-old sprains her

left ankle. Initially, the pain was confined

to the child's left ankle, but over weeks, it

spread to involve the entire left lower extremity.

Associated with the pain the child reported

cold sensation in the leg, whitish to reddish

discoloration of the skin and increased sweating

in the left foot. Also, the patient complained

of increasing sensitivity to light touch causing

pain in the effected region of the leg.

The patient was evaluated by a Pediatrician,

Orthopedist, Rheumatologist and a Neurologist

without arriving at a diagnosis. When examined

at the University of South Florida, lightly

touching or stroking of the skin provoked pain

and she was unable to bear weight with the left

leg.

|

| Lacey

was confined to a wheelchair |

The child was confined to

a wheelchair. Using a portable infrared scanner,

the child's left lower extremity was profoundly

colder than the right by 2° degrees centigrade.

Published data and consultant opinions indicated

that a series of one to three sympathetic nerve

blocks may reduce the risk of progression of

RSD. Sympathetic nerve blocks are particularly

urgent when the patient is immobilized with

pain. In this patient's case the child was unable

to bear weight with the left lower extremity

and she was confined to a wheelchair. The child

became progressively worse, despite administration

of pain medications, aggressive Physical Therapy,

and treatment by a Psychologist to help her

better cope with the pain.

The child underwent a series of three lumbar

sympathetic blocks spaced approximately 1 week

apart. The child made only slight improvement

in her condition. At that point a meeting was

held with the family and child to discuss the

child's treatment options. At that meeting an

approach to her treatment was recommended that

ultimately led to a nearly full recovery from

RSD.

Recently, Dr. Kirkpatrick met with the child

and mother for a progress report. This interview

was not recorded in a studio. In fact, Dr. Kirkpatrick

simply placed a camera on the corner of his

desk and began recording. What the interview

might lack in technical quality is more than

made up for in the honest and spontaneous responses

of the child and mother.

(Interview Begins):

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

After we finished doing these blocks on you

we had a meeting, do you remember, in my office?

Lacey:

Yes.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Yeah

Lacey:

Mom lost her keys.

Lacey's Mother:

I lost my keys.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

That's right! That's a good memory, you have

a good memory. You remember. That's right. Now,

see if you can remember that meeting. What do

you think...what was it that I was trying to

emphasize? What do you think I was trying to

communicate at that meeting? Do you remember?

Lacey:

No.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

You don't remember? Okay. Well, I think one

of the things is that your response to the sympathetic

blocks was nothing to write your mother about.

You seemed like you were doing better, but we

weren't really sure and I said it's better not

to guess about these things...Let's just say

that your response to the blocks was not very

good.

(Lacey nods her head)

Now, you don't remember what I suggested what

we needed to emphasize at that point, do you

remember what I said we need to work on, some

ideas we need to try to develop...do you remember?

|

| Lacey

and her mother discuss RSD |

Lacey:

You said something about Physical Therapy.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Okay.

Lacey:

You said something about needles.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Okay. What did I say about Physical Therapy?

Do you remember?

Lacey:

You said I might need to start walking.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Yes, and what else did I say?

Lacey:

I don't remember.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Okay, alright. I don't know if your mom can

remember. (To Lacey's mom) Do you remember some

of the ideas that we talked about?

Lacey's Mother:

I think we talked about her getting in the pool...um...I'm

not sure I remember...

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Yes, that was an important meeting to me, and

so it was an important meeting because I wanted

you to get better. And I had a feeling that

I knew what was going to be required to make

you better. And let me tell you what I recall

having said to you and your husband and to Lacey

and that's this: It is understandable why you're

very reluctant to put weight on that foot. It's

very understandable, and your parents needed

to understand, because when you hurt with RSD

it is like no other pain you can imagine, wouldn't

you agree with me?

Lacey:

Uh huh. (Shakes her head yes)

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

And when you complain of pain everyone has to

respect that. I think your mom remembers me

saying that, it ...

Lacey's Mother:

Uh huh.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

...that it's not that you're not being a big

baby or anything like that, but that it hurts,

and it hurts like no other pain that anybody

can experience, especially a child. And I said

that it's normal not to want to move on it,

it's normal. It's normal not to put weight on

it because, you know, that's how we protect

ourselves when we're hurt, right?

Lacey:

(Nods her head yes)

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

If we kept stepping on glass on the floor, we

would bleed to death, right? So that was very

normal for you to do that. But do you remember

me saying something to the effect that, something

along the lines that...

Lacey:

It wouldn't hurt you.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Very good Lacey. You do have a good memory.

You do have a good memory.

Lacey's Mother:

You said, To hurt is not to harm.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

That's right, we said that. To hurt was not

to harm. But, I also said that you shouldn't

be forced to do that when you're hurting, that

it has to come from you. You have to understand

that, and it isn't easy is it? Be honest?

Lacey:

(Shakes her head no)

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

It's not easy is it?

Lacey:

No.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

It's not easy because...especially for a child.

I mean, we...as adults...we can put our minds

and say, I believe Dr. Kirkpatrick, and he's

saying it's not going to harm me, it's not going

to break my bones and ruin my tissues and everything.

I could probably talk you mother into that idea,

but try to talk a child into that idea? Wouldn't

you agree with me? It's not as easy to do a

child?

Lacey:

(Nods her head yes and smiles)

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Because you haven't had a lot of experience

in life. I mean like 10 years. You know what

I mean? Right?

Lacey:

(Nods her head yes and smiles)

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

So, what did you do? I mean, apparently you

did something. How did it happen that you started

moving? Give me an idea, what happened?

Lacey:

Well, umm... mom said we were going to move

from our house if I didn't get out of the wheelchair,

because our house has lots and lots of stairs

and I couldn't do that in a wheelchair. So,

in the pool, I started walking in a pool. And

at first I couldn't do that, and then I could

do that. I started walking up the steps in the

pool with mom holding on to me. Then me and daddy started walking up the steps in the pool.

And then, one day I got out the crutches and

tried to walk, try doing one foot first then

the other. It wasn't really too bad, but it

hurt a lot. So, I went and showed mom. And then

when I was in with mom I did something and it

made it hurt so bad. You remember that, don't

you?

Lacey's Mother:

Uh huh. (Nods her head yes)

Lacey:

She was in the bed. She was watching me going

around the bed, and I was on the corner of the

bed, I'll go, OW! And I guess I hopped a little,

because when I go on crutches I kind of hop.

So, I guess I hopped a little and that really

hurt it, but I just kept doing that, and eventually

I got to where I could walk, slowly.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Slowly?

Lacey:

Um, like just little teeny steps. And I got

to where I could walk bigger steps cause I said

to myself, Why walk teeny steps cause it's going

to take you longer to get there, and it's going

to take you longer to get off your feet. So

I started walking big steps, and it wasn't really

bad.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Uh huh.

Lacey:

And that's how it happened.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

How long ago was it roughly? How long ago was

it that you were doing these teeny...because

I didn't see any teeny steps today. I didn't

see any teeny steps. How long ago was it that

you were doing teeny steps, roughly, would you

say?

Lacey:

Um...I don't know.

Lacey's Mother:

It was in July.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

In July?

Lacey's Mother:

Uh huh. (Nods yes)

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

So, here we are in October...so, we're talking...3

months ago, roughly?

Lacey:

(Nods her head yes)

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

So, you've made some significant improvements

since then. Now, how about this. What about...umm...tell

me about some of the things you're doing nowadays.

I mean, I heard some things about some things

that you've tried that are pretty challenging

physically, right?

Lacey:

(Nods her head yes)

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Okay.

Lacey:

Um...me and mom have been riding our bikes a

lot.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

You...you ride a bike a lot?

|

| Lacey

makes a full recovery |

Lacey:

We have a long dirt road and it's got a big

hill, and I'm the only one that can get up the

hill without stopping now, so... And I do a

lot of running with my friends. And I do Girl

Scouts. And sometimes in Girl Scouts there's

stuff where you run and jump, so that kind of

helps.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Uh huh.

Lacey:

And...

Lacey's Mother:

Jump Roping.

Lacey:

I jump rope a lot.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Do you? Good for you.

(Interview ends)

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

It is difficult to know exactly how much the

recovery in Lacey's case was due to the series

of sympathetic blocks, and how much was due

to the psychological conditioning that she received.

The adage to hurt is not to harm is an important

principle, however, this principle should be

applied keeping in mind this:

First: The cornerstone in the treatment of RSD

is normal use. The patient needs to mobilize

the effected extremity as much as possible.

Second: Often the Physical Therapist will treat

the patient with RSD with passive manipulation,

causing failure due to extreme pain, even possible

further injury.

Third: learning the non-protective nature of

pain takes time.

Fourth: While encouraging the use of the effected

extremity is critical and may cause increased

pain, it is essential to avoid re-injury.

In contrast to the minimal response to sympathetic

blocks observed in Lacey's case, the next child

illustrates how crucial sympathetic block aid

is to the rehabilitation of a child with Reflex

Sympathetic Dystrophy.

(New case, Amanda)

Imagine that your child is a National Champion

in Gymnastics, even offered a scholarship to

a major University, when, at the age of 10,

all that comes to a crashing end due to a gymnastics

accident. That is the case of Amanda.

Amanda first suffered an injury to her right

wrist; it was a minor sprain of the wrist. The

RSD spread up her arm to include her shoulder.

She required a series of sympathetic blocks.

Unfortunately, the sympathetic blocks did not

provide her with a permanent remission; therefore,

she had to have a Sympathectomy to the right

upper extremity. Subsequently, the patient injured

her left lower extremity, a simple sprain to

the ankle. Again, the symptoms spread up the

leg to include the buttock region as well.

A series of sympathetic blocks were offered.

Again, the patient did not sustain a permanent

remission and had to undergo a sympathectomy

to the left lower extremity as well.

More recently, the patient injured her right

lower extremity and required a series of sympathetic

blocks. Currently, the patient is undergoing

these sympathetic blocks to sustain mobilization

of her right lower extremity.

(Anatomy of nerves demonstration)

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

In order to perform a sympathetic block to the

upper extremity, a needle needs to be inserted

near the neck in order to block the nerve, the

Stellate Ganglia, which sits down, actually,

in the chest. For the lower extremity, the sympathetic

nerves, again, lie along the spine and it is

necessary to insert a needle into the back,

and come down and block the nerve in this location

here. It is important to recognize that the

sympathetic nerve, indicated here by these little

red dots, are separated from the nerves that

you feel and you move with, your Sensory and

Motor nerves. Therefore, it is possible to block

the sympathetic nerves without blocking the

motor and sensory nerves. Therefore, after a

sympathetic block, the patient should experience

simply a warming of the extremity and not any

change in movement, or in their ability to feel

things. necessary to insert a needle into the back,

and come down and block the nerve in this location

here. It is important to recognize that the

sympathetic nerve, indicated here by these little

red dots, are separated from the nerves that

you feel and you move with, your Sensory and

Motor nerves. Therefore, it is possible to block

the sympathetic nerves without blocking the

motor and sensory nerves. Therefore, after a

sympathetic block, the patient should experience

simply a warming of the extremity and not any

change in movement, or in their ability to feel

things.

(Sympathectomy explained)

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Sometimes a series of sympathetic blocks is

not sufficient to maintain a permanent improvement

in the patient's condition. Under these circumstances

a permanent block, or sympathectomy, is necessary.

For the upper extremity, one can come in between

the ribs with a scope, find the nerve along

the spinal column, and remove it. For the lower

extremity we have two choices. We can go in

with a needle and dissolve the nerve with a

chemical called Phenol; or surgically, we can

do an excision by going in and actually removing

the nerve from the patient's body.

Another issue of special concern to children

is fear of nerve blocks. In this portion of

the interview, Amanda discusses her experience

with Intravenous Sedation and nerve blocks.

In children, sedation is usually provided during

sympathetic blocks. Combinations of Midazolam

and Propofol have successfully been employed

to relieve anxiety. Unfortunately, larger doses

of these agents are required to prevent movement

during the procedure. This can leave the child

with an unpleasant feeling of a Hang-Over. We

have successfully added small doses of Ketamine,

which intensifies the sedation, decreases the

amount of Midazolam and Propofol required, and

thus prevents the feeling of hang-over. In addition,

recent studies showed that small doses of Ketamine

actually increased breathing, thus increasing

the safety margin for deep sedation.

Let's hear from Amanda about her experience

with deep sedation and nerve blocks.

(Interview with Amanda about sedation and blocks

begins)

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Now, one of the things that you know, again

we're dealing with children, is the fear, the

fear of having treatments and you've been through

a lot, a lot of nerve blocks. I mean, you added

them up young lady, we're talking big time.

I mean, if you said, I had 50 or 60, I mean,

I didn't do all those, but you know, you add

them up. There's been a lot of nerve blocks,

sympathectomies, upper and lower.

Amanda:

Yeah.

|

| Amanda

Alberigi and mother discuss RSD |

Amanda's Mother:

Yes, Right.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

I mean, there's been a lot going on here. I'm

just wondering do the nerve blocks scare you?

Amanda:

No. The first time maybe, yeah, but...

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

After a while...

Amanda:

I trust you.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Tell us, not about the trust; tell us about

the block. You know, when we treat you we use

a medication. We don't use it alone; we use

it with a sedative, okay?

Amanda:

Uh huh.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Versed, Midazolam...

Amanda's Mother:

Versed.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

And we use Ketamine. And the reason we use Ketamine

is because it helps keep you breathing. And

one thing we know about children, young people,

they need a lot of oxygen. And I mean they burn

oxygen like crazy and if they don't get oxygen,

they go blue real fast, you know? So, Ketamine

is the drug we use. Now, when we give you Ketamine

is there anything about it that you, uh...for

example: some people dream, some people don't.

Do you ever dream with it?

Amanda:

No.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Do you ever have any...do you recall any...uh...well...not

dreams, but just the funny feelings like colors

or anything like that? No?

Amanda:

No.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

No? You're just out?

Amanda:

Out for the count.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

You're out for the count.

(Interview discussion about sedation and blocks

ends)

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

It is worth emphasizing that Ketamine should

never be used alone. It should be used with

other sedatives; otherwise the child may awaken

in an uncomfortable state. The IV should be

inserted in an area other than the procedure

room. The procedure room can be a very threatening

environment. In addition, parents may unintentionally

generate fear in the child if they fear needles

themselves. Therefore, it might be best not

to have the parent present during the insertion

of an IV.

Cosmetics, or scar formation after surgery,

is another concern to children. Amanda addresses

some of these concerns during the interview.

(Interview with Amanda about cosmetics/scar

formation begins)

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Lets talk about another thing that you, only

you can...probably more than anybody else I've

ever seen...perhaps help understand a concern

that children have. And that is, you eventually...after

the Phenol didn't take long enough...you ended

up getting a surgical, a surgical sympathectomy

done. And of course, young people, appropriately

fear a scar. I mean, you know, bikini's are

sort of like in and that sort of thing.

Amanda:

(Nods her head yes)

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

So Amanda, tell me about that.

Amanda:

My, uh...the scars don't bother me really. I

don't even realize they're there sometimes.

I mean, the ones that I have under my arm, they're

healed pretty well, except the chest tube one.

It's still there, but...

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

It's still there?

Amanda:

...and they don't bother me.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Now suppose you want to make an appearance.

I'm sure if it was you or some other child,

that there's a way you can cosmetically conceal

it a little bit. Uh...I've been told, of course

I'm no expert at this, but I've been told...

like... for example when women have breast implants,

that they can put this little tape and stuff

on it.

Amanda:

Uh... that's the most painful thing I've ever

had to go through in my life.

Amanda's Mother:

We've tried it.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Oh, you've tried it. Okay.

Amanda:

We're not doing that.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Well tell us. What happened?

Amanda:

I did it with my chest tube one and it hurt.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Oh, it's painful? Really?

Amanda:

When you have to rip it off it hurts. Yeah,

it hurts!

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Oh, in other words you put it on temporarily

for whatever the...

Amanda:

Right. 24 hours.

Amanda's Mother:

Right. It's a patch and you wear it for 24 hours

and you have to take it off. It did reduce the

swelling and the color, because it was a raised

scar... and it healed from the inside out...so

it was raised. To where the one on her stomach,

which is still very sensitive, we haven't even

attempted that. But she kept Vitamin E as well

as 50 sun protector, being out in the sun during

the summer...

Amanda:

I show my scars.

Amanda's Mother:

...and she doesn't hide them. She doesn't let

them bother her.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Yeah, yeah...well let me ask you this now, if

I understand, because I've never seen this technique.

Amanda:

It's called a silicone patch.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

That's what it's called, a silicone patch?

Amanda:

Uh huh.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Now, does it leave like...you put it on ...it

has to be on for 24 hours and you take it off?

Does it leave something there on your skin?

Is that what it's supposed to do?

Amanda's Mother:

I don't know.

Amanda:

You have to replace them every 24 hours.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Every 24 hours?

Amanda and her Mother together:

Yes, yes. Replace them for 30 days.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

So, it's not a patch you put on and leave on

to cover it up, but when you take it off, that's

the final product?

Amanda:

It reduces the scar more and more.

Amanda's Mother:

It shrinks it.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Oh. It shrinks the scar. Oh, I see. But what

you're saying when you gave it a try just for

fun, whatever, it was painful taking it off.

Amanda:

Yeah. It feels like ripping a band-aid off,

just ten times bigger.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Right, right...

Amanda's Mother:

Because the patch is about that square, 5 by

3 square.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

I see. So the Sympathectomy to the left lower

extremity was done about 14 months ago...

Amanda:

No.

Amanda's Mother:

No, no, April 2nd.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

April 2nd...

Amanda's Mother:

April 2nd, 2001. Seven months ago.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

7 months ago. Now, can you show your scar here

so we can see it?

Amanda:

Yes.

Amanda's Mother:

Don't show the belly button ring.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Oh yeah. Let me see if we can get a little close-up

of that. There we go. Alright. So, that's the

scar and you did say that you tried to apply

that...

Amanda:

Not to this one.

Amanda's Mother:

Just Vitamin E and sunscreen.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Yeah. Without getting too private, is there

a...can you show the other one?

Amanda:

Here's one.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Yeah, let's see. That's only one, there should

be three.

Amanda:

There's one under my breast.

Amanda's Mother:

But you can't hardly see it.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

You don't have to show us the one under ...

Amanda's Mother:

You can't hardly see them.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

You don't even see them. Put your finger on

the one there. There's one there. Let me see

if I can zoom in on that. Let me go up there.

Let me see. There's one up there; that little

guy.

Amanda's Mother:

That's where the chest tube was.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

That's where the chest tube was...

Amanda:

...and then there's...you can't see the other

ones...

Amanda's Mother:

No it's...

Amanda:

You can't even see it.

Amanda Mother:

No, it's...you can't even see it.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

So she's only left with 2 scars. Well, that's

interesting. So, the one that leaves most of

the scar appearance is really the one that is...

Amanda:

On my stomach...

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

On your stomach, yeah. So that's important you

know. I mean, that scar appearance is really

the one that is...

Amanda:

On my stomach.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

On your stomach, yeah. So, that's important

you know. I mean that we recognize and be able

to tell young people, Hey, if you're going to

have a surgical sympathectomy, you're going

to get into something a little more substantial.

Amanda:

Uh huh.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Now tell us this, you know you've had both.

When you look back at your recovery from the

two, which one was the more difficult one after

surgery to deal with, would you say?

Amanda:

The one in the upper area.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

It was? Why is that?

Amanda:

Because I was in ICU for 24 hours with a chest

tube.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

With a chest tube?

Amanda:

And that was rough.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

That was rough?

Amanda:

That was very rough.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

And they gave you pain medicine for that?

Amanda:

They gave me Morphine, but I didn't want it

anymore. So, I was just taking Tylenol.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Yeah, because it makes you kind of dopey? Is

that the reason?

Amanda:

No. It made me sick.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

It made you sick, like nauseated?

Amanda:

Oh yeah.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Yeah, um...but... well of course, we all know

that for the lower one...for the lower one...on

the lower part...that one, you were out the

next day I believe, out the door.

Amanda:

Uh huh.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

You know, this is kind of interesting, because

you know what? In adults, it's the other way

around.

Amanda's Mother:

That's what Dr. Bandyk told us. He said, My

patients don't usually go home for 4 days.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Yeah. They're out of the hospital faster for

the upper extremity sympathectomy than for the

lower one. And that's a difference, and that's

a difference that's very important.

Amanda's Mother:

We were in the hospital for 5 days for the upper

and less than 24 hours for the lower. And she

was up walking around the same night that she

had the lower one.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Yeah. What I'm planning to do here is, you know,

I have the video of that little worm they took

out of you.

Amanda's Mother:

Yes.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Did I send you that video?

Amanda's Mother:

Yes you have.

Amanda:

Yes.

|

Laughter

occurs when the family learns that

Amanda's surgery will be part of the video

program |

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

I'm going to try to get that inserted in here

so that we can look at it. Now, is there anything

else that we could... have we missed anything

from the mother's point of view? What do you

think? Is there anything else that's important

having gone through all of this?

Amanda's Mother:

Think positive and be strong. Trust your doctor.

I mean, they're the only ones that know what's

really right. I mean, and if she wasn't comfortable

in any of the decisions...I always let her be

involved in the decisions, because that's...it

was her body, it's her that it's happening to,

not me. So, I can't be the one to say, well

this is going to fix it, let's do it , and I

let it be her decision. So I think it's important

she, you know, each child needs to. But they

need to know the repercussions of, you said,

the scars, you know? Are they so vain they don't

want the scars, and do they want to just have

the pain? Do they just want to deal with it

or do they want to get better.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Yeah.

Amanda's Mother:

And knowing that this was the best way to get

better, we made the decision, and we made a

very reasonable decision to have it done.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

So Amanda, what's your take on it? Do you agree

with that?

|

Amanda

is cured of RSD in her right upper

extremity by sympathectomy |

Amanda:

I do. You've got to be positive, you can't think

negatively.

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Yeah.

Amanda:

You can't think negatively.... (Inaudible)

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Right.

(Interview with Amanda ends)

(Dr. Bandyk discusses sympathectomy)

|

Dr.

Dennis Bandyk explains the risks,

limitations and potential benefits |

Dr. Bandyk:

It must be emphasized when undertaking more

invasive approaches to pain management such

as sympathectomy, that the benefits must be

carefully weighed against the risks. Recently,

we reported on a large series of patients with

RSD at the University of South Florida that

had undergone sympathectomy. Over 3/4 of the

patients had long-term benefits from the procedure.

However, other patients did not obtain significant

long-term benefits despite very careful selection

for sympathectomy.

Furthermore, it should be emphasized that there

is little published data on sympathectomy in

children. Therefore, extra caution is prudent

when considering sympathectomy in children until

more data becomes available.

The selective use of these invasive treatments

must be by a very experienced physician. Before

considering a sympathectomy, a child should

be offered a series of pure sympathetic blocks

to help facilitate an informed consent about

what to expect from a sympathectomy. An epidural

block is not a pure sympathectic block.

Before considering an invasive procedure the

family should be encouraged to obtain a second

opinion to ensure that all lesser invasive therapies

have been tried. In Amanda's case, her multiple

extremity RSD consistently forced her to be

absent from school within one week after each

sympathetic block. Pain medications, aggressive

physical therapy and extensive psychological

counseling all failed to control her RSD symptoms.

Now it appears that she has been cured of RSD

in both her right upper and left lower extremities

following sympathectomy to those regions of

her body.

Children will fall into several groups. First

are those who are permanently cured by treatment.

The second is a group of children whose conditions

are improved, but then show a high recurrence

of RSD. Fortunately each subsequence occurrence

of RSD seems less severe. A third and relatively

small group of children with RSD get progressively

worse despite treatment and require aggressive

intervention, even sympathectomy. In this last

group of children with the most severe form

of RSD, physicians may procrastinate and wait

until the skin of the extremity turns from blue

to black, indicating irreversible tissue loss,

before considering a sympathectomy.

Once a disease is allowed to progress to this

advanced stage, it may be too late for a sympathectomy

to provide any improvement in tissue perfusion,

or prevent the need for an amputation.

A sympathectomy should be considered before

such severe dystrophic changes occur in the

tissues of a child with RSD. It is often difficult

to know in advance if a child falls into this

more severe form of RSD, therefore, vigilance

is required in following the clinical course

of RSD in children, in order to achieve the

best outcome.

Recently, the surgical technique for sympathectomy

has been modified to minimize scar formation.

For example, the need for insertion of a post-operative

chest tube is being eliminated in some patients.

And the laparoscope is now being used to perform

Lumbar sympathectomy of the lower extremity

as well.

(Dr. Bandyk's discussion ends)

(Dr. Kirkpatrick's discussion begins)

Dr. Kirkpatrick:

Some children with RSD improve with conservative

treatment. Indeed, the available pediatric literature

supports the notion that a high percentage of

children will improve with active mobilization

of the affected extremity and psychosocial conditioning

alone. There is a definite art to guiding a

child through a step-wise return to weight bearing

and mobilization of the effected extremities,

and for helping them to understand the difference

between protective and non-protective pain.

As shown in this video program some children

benefit significantly from pool exercises.

According to a recent study at Harvard Medical

School, one needs to remain vigilant for a recurrence

when a child goes into remission following a

bout with RSD. In that study, recurrent episodes

of RSD in children occurred in up to 40% of

patients, however, most of these recurrent episodes

were milder than the initial episode.

A variety of medications are helpful for individual

children, but there is no perspective pediatric

literature on specific effectiveness of most

of these agents for this type of pain found

with RSD. Trials of anti-depressants such as

Nortriptyline might be useful as adjuncts for

sleep in many patients. Anticonvulsants such

as Gabapentin are sometimes helpful. Several

patients have had good responses to a short

course of Prednisone early in a flare-up; others

have not. Clearly, further research is needed

to determine what is the most effective treatment

options for children.

Another important point, in several case series,

a high percentage of children with RSD have

been very involved in sports, dance and gymnastics.

Indeed, the thought of gymnastics competition

often conjure images of major trauma as shown

in these short video clips. It must be emphasized,

however, that most children that engage in gymnastics

or similar sports do not get RSD. The fact is,

RSD can be triggered by a relatively minor injury.

We would like to give special thanks to Lacey

and Amanda for the significant contribution

they've made to educating us about RSD.

Male Narrator:

Some key points made in this video are worth

emphasizing:

The pathophysiology of RSD is uncertain. The

animation presented during the early part of

the video program is at best an over simplification

of how RSD develops following injury. In fact,

some refer to RSD as a Complex Regional Pain

Syndrome to avoid the implication that the disease

has to involve a reflex of the Sympathetic Nervous

System. These two pediatric cases illustrate

that there is great variability in the clinical

course of the disease as well as variability

in the response to treatment. The importance

of time in treating RSD needs to be stressed.

Do not expect change overnight. Active participation

of the child is crucial.

It needs to be emphasized that this video is

a case-report about two children who have had

to struggle with RSD. The video program is not

intended to be a comprehensive review of the

treatment options available for children with

this disease.

The video glossed over fairly quickly medication

trials, cognitive and behavioral approaches

to pain, which are the meat that help the majority

of children with RSD.

As with sympathectomy, there are other invasive

treatments such as Spinal Cord stimulation that

might be applicable to only a small minority

of children with RSD. Because everyone is different,

the information expressed in this video program

cannot and should not be used to diagnose or

treat individual health problems in patients

with RSD. The treatment must be individualized

by a health professional.

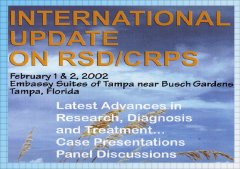

|

This

video program underwent extensive

peer review at the international symposium

held at the University of South Florida |

A 30-minute version of this

video was presented and peer-reviewed by an

international panel of experts on RSD, at the

International Update on RSD / CRPS, held at the

University of South Florida. As a result of

the comments received by this panel, the video

was expanded to 40 minutes in order to cover

a broader range of issues in the diagnosis and

treatment of RSD.

For complete guidelines for the Diagnosis and

Management of RSD, please refer to the Clinical

Practice Guidelines available on the Internet

in English, Spanish and French published by

the Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy Syndrome Association

of America and by the International Research

Foundation for RSD / CRPS. The Scientific Advisory

Committee on RSD wrote these guidelines.

We hope you found this overview of RSD in children

helpful. |

|

|

HOME | MENU | CONTACT

US

The International Research Foundation

for RSD / CRPS is a

501(c)(3) (not-for-profit) organization in the United States of America.

Copyright © 2003 International

Research Foundation for RSD / CRPS.

All rights reserved.

For permission to reprint any information on the website, please contact

the Foundation.

|